Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue

Stockholm-based Johanna Gustafsson Fürst is the third artist to exhibit at the new exhibition space and the first to present sculptures and installations in all of Accelerator’s exhibition spaces. Gustafsson Fürst’s art deals with the connections between social systems and individuals. In the development of Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue, she has been concerned with how power is exerted through language, and the relationship between language and body.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue". Photo: Gustaf Nordenskiöld.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue". Photo: Gustaf Nordenskiöld.

Installation view from the second part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst's exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Installation view from the second part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst's exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst "The Library", 2020. Installation view from the second part of the exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst "The Library", 2020. Installation view from the second part of the exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

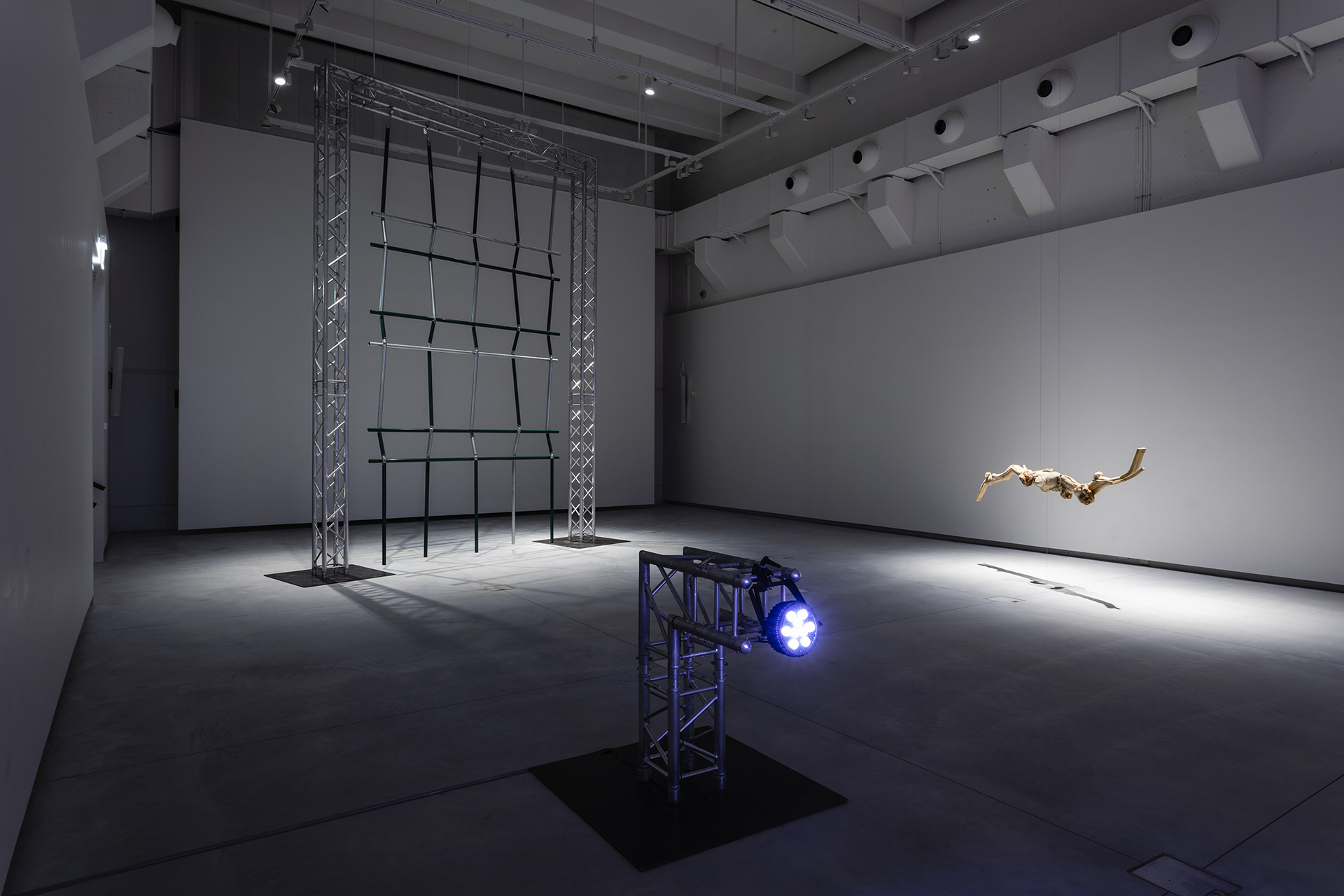

Installation view from the first part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst's exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Installation view from the first part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst's exhibition "Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue" at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

About the exhibition

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst’s practice is characterised by dialogue: with materials, spaces, other professional groups, poetry, colleagues and places. The attempt to understand complex contemporary events and social relationships is embodied in her sculptures. Her work is rooted in site-specificity and self-organisation, often in long processes in public. The various, constantly ongoing dialogues in Gustafsson Fürst’s work create a fluid process that takes great consideration to events at the exhibition site. With the ambition of providing space for a long-term dialogue with the artist, that could incorporate her fluid work process, Accelerator chose to invite Gustafsson Fürst to participate in a dynamic exhibition format that could develop over time. The exhibition Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue is structured as a two-part drama in which several works will take on a different form and new works will be added in part two. Part one of Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue was primarily characterised by the normative oppression exerted by monolingualism, the relationship between language and body, and how multilingualism enriches. The second part will focus on collective participation and the management of language via libraries and archives. The two parts may be regarded as two perspectives on, or conditions of, the same topic and they may be experienced separately.

Language violence and subject formation

Work on Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue began in the summer of 2018 when Gustafsson Fürst spent a research period in Lainio in Norrbotten, close to the Finnish border[1]. She describes how she met people who had been affected by the language violence that was part of the Swedification process of Tornedalen, which began when Sweden lost Finland in 1809. In the 1880s, all teaching in state-sponsored schools was in Swedish, which meant that other contemporary languages were de facto banned from schools and libraries. The result was that school children were deprived of their ability to communicate. Gustafsson Fürst became concerned with how such an experience affects subject formation and the intimate conflation of body and language. In today’s Sweden, bills have been introduced in parliament proposing a ban on speaking other languages than Swedish on breaks in elementary schools, as well as withdrawing mother-tongue education. The discrepancy between such language policies and the encounter with language-loss experiences and the promotion of pluralism has been central to the creation of the works in the exhibition.

The title Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue derives partly from a poem by Bengt Pohjanen, and partly from the work process in the studio in which the synthesising of bentwood according to the method of grafting became a metaphor for how languages infect and disseminate into each other. In the poem Jag är född utan språk [I was born without language], Pohjanen writes[2]:

Jag är uppväxt vid gränsen [I was brought up at the border]

i korseld mellan två språk [in the crossfire between two languages]

som piskat min tunga [that have whipped my tongue]

till stumhet [into silence]

Borrowing the words whip and tongue, Gustafsson Fürst chose to create a bidirectional movement. It is an exhortation for one’s own tongue to whip, to act, and at the same time a masochistic prayer for a linguistic challenge.

[1] The research trip was part of the artistic initiative Residence-In-Nature: a cross-disciplinary project initiated by Åsa Jungnelius where artists are invited to work with a specific locality. Residence-In-Nature in Lainio was organised by Hans Isaksson, Åsa Jungnelius and Lisa Torell.

[2] From Bengt Pohjanen’s poem Jag är född utan språk [I was born without language], Vår Lösen, 1973:3. Bengt Pohjanen writes novels, plays, film scripts, songs, poems and librettos in three languages: Swedish, Meänkieli and Finnish.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst" I am fascinated by how language intertwines our bodies and societies, and, above all, how it feels when language is broken down, and what the consequences are. What does the linguistic violence exerted by governments to maintain and expand the nation state do to us? Although many people are aware that language is changing perpetually and is stimulated by diversity, there are calls for uniformity, through cutbacks in teaching first languages, for instance, and demands that proficiency in Swedish should be a condition for citizenship. "

Works in the exhibition part 2

The Library, 2020

In the first part of the exhibition, the 21 bentwood sculptures were installed alone in the gallery. The installation has now been densified with benches, the publication Stridsskrift and sections of a fence supported by aluminium. Together they constitute the installation The Library. Archives, museums and libraries that house accumulated knowledge, compiled under thousands of years, are part of what makes us human. Books on Judaism, Nazism and LGBT issues were burnt outside Linköping City Library during the night of 27 January 2020. The collections of the International Library in Stockholm are broken up. The Swedish Library Act 2 § states: “Public libraries shall be accessible to everyone”. Visitors are invited to sit down on the benches and read the book Stridsskrift.

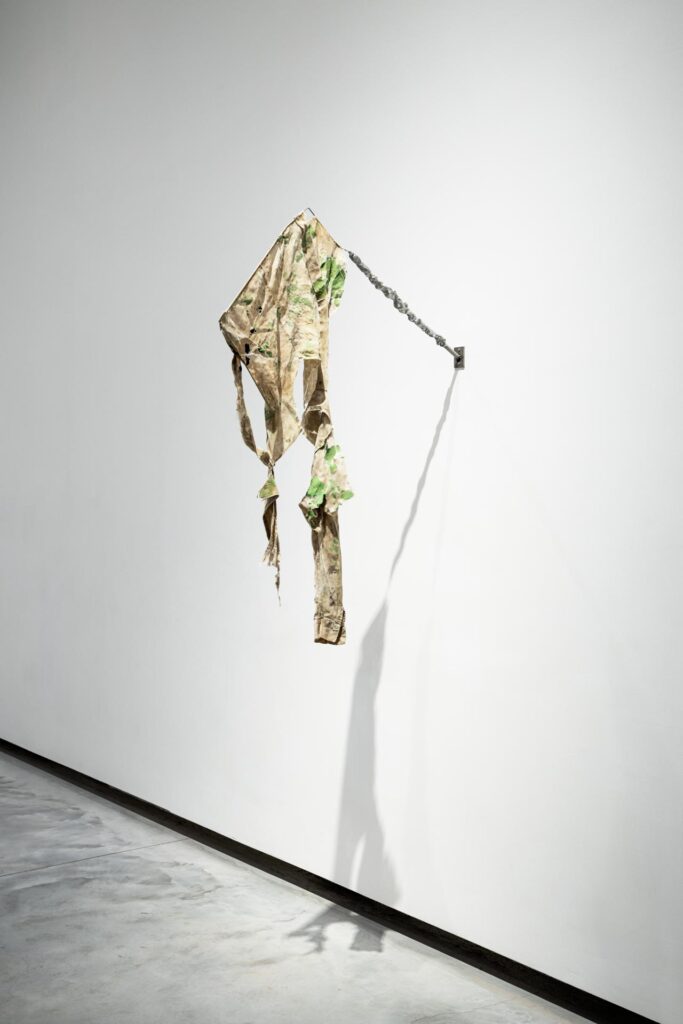

Untitled, 2020

A piece of fabric found on the shore of the Baltic Sea on the southern tip of the island of Öland has been installed like a flag. All the world’s sovereign states have a national flag and rules governing its usage. A flag could be described as a tool for collectively manifesting a common cause: a battle, a struggle, a loss, a victory, a jubilee. The sculpture has no title and the fabric has no motif.

Monolingual Territory, 2020

The sculpture Monolingual Territory comprises black-lacquered bentwood objects from a found piece of furniture, and cast aluminium mounted on the wall in a gun rack. Hose clamps, used to seal a hose, gird the bentwood. Tools and methods employed in Sweden to establish a monolingual norm have varied throughout history. The first Alphabet book, for example, was an important instrument in the Swedification of Skåne in the 17th century. In our time, the methods are expressed as bills introduced in parliament to restrict mother-tongue education. In Sweden today, some 200 languages are spoken and written.

Paroll Parole Parole, 2020

The installation Paroll Parole Parole has a trilingual title: ‘Paroll’ in Swedish means ‘slogan’, In English ‘parole’ means ‘early release of a prisoner’. The French ‘parole’ means ‘everyday speech’. ‘Parole’ is also a concept created by the renowned Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913). He divided language into two parts: Langue and Parole. ‘Langue’ was the linguistic system of alphabet, grammar etc, while ‘parole’ was the application of these rules. ‘Parole’ is the active language, the actual speech that we hear in real life. Rigid materials from public space are suspended motionless from a structure. They do not limit or restrict; we can move in between the gaps of the structure.

The Wave, 2020

The word ‘wave’ may refer to an elemental force, a movement or a trend. The waves of the sea may provide opportunities for play or constitute a threat, as in a tsunami. ‘Wave’ is also a part of words, as a ‘soundwave’, or a concept such as ‘fourth-wave feminism’. An unstoppable elemental force, an invisible movement without its own moral or agenda, or a gathering force that brings people together to collaborate towards a common goal.

The Invisible Order, 2020

The first work visitors encounter in the exhibition is The Invisible Order, 2020. The work features sections of a fence installed in a v-shape. In public space, fence sections are a directional structure, aimed to protect or to confine.

Works in the exhibition part 1

VOX, 2020

The first work the viewer encounters in the exhibition is VOX, 2020. Vox is Latin for ‘voice’. The installation comprises various elements that disseminate into all the galleries of the exhibition space. Modelled aluminium poles and distressed barrier tape create obstructions. A piece of fabric found on the shore of the Baltic Sea on the southern tip of the island of Öland has been installed like a flag. A steel rack covered by reflective fabric is illuminated by a spotlight that lights up the reflector and, at the same time, blinds. Language is a constant, collective negotiation in which words and dialects continuously appear and disappear. The work assumes different forms depending on the position of the viewer.

L/anguish–But if the Word Gags, Does Not Nourish, Bite it Off, 2019

The installation is composed of 21 sculptures in which parts of bentwood have been synthesised using various grafting methods. The bentwood, which in itself has been elaborated into shapes beyond its organic capacity, has, in the sculpture, been further compressed until cracks and tears appear. Grafting is a method in plant breeding. A foreign part is united with a growing plant by insertion. For example, grafting makes it possible for several types of apples to grow from one tree. Grafting is both enriching and violent. Gustafsson Fürst has returned to the idea of banning or confining a language as a kind of mutilation in contrast to the proliferation by grafting. The title is composed of two synthesised fragments from two poems in the collection She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks (1989) by poet M. NourbeSe Philip: “L/anguish” from the poem Discourse on the Logic of Language and “but if the word gags, does not nourish, bite it off” from Universal Grammar.

The ABC-book, 2020

The exhibition process set out from the experiences of language loss that Gustafsson Fürst encountered in Norrbotten. The ABC-book is a work that began as an in-depth study of language policies as an instrument for constructing a nation. In 1611, Johannes Bureus created Sweden’s first alphabet book for schools, a primer on national language teaching and a Swedification tool, which has appeared in various versions since then. In the work, steel fence sections have been joined together into a mesh. In a public environment, fence sections constitute a directional structure. A tool for public administration in order to protect or constrain. The question of how a language system is interwoven and how individuals encounter and are woven into the system has been central to Gustafsson Fürst.

The Mothertongue, 2019

The title The Mothertongue is borrowed from the English mother tongue, one’s native language. Gustafsson Fürst notices with interest that the English word points to the assumption that a specific language is related to origin and body. The development of a language is an organic and changeable process of synthesisation with no a clear beginning or end. A language is always in a state of flux and if one is raised in a multilingual environment one has several “mother tongues”. In the sculpture, chair components and burls from Norrbotten have been synthesised. In some sections, the material has been carefully ground to achieve a seamless body; in other sections, the breaks are clearly visible.

– Therese Kellner, Curator

The book Stridsskrift

The second part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst’s exhibition Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue at Accelerator will coincide with the launch of the book Stridsskrift, edited by literary critic and author Sara Abdollahi. At an early stage in the exhibition process, Gustafsson Fürst expressed the importance of providing space to explore the themes of the exhibition in literary texts: “I wanted to bring together a group of people who use language as their medium for an expression of the joy of words, the pain of having one’s language restricted and the need for linguistic freedom and difference”. In collaboration with Sara Abdollahi, Gustafsson Fürst invited the writers and poets Lars Raattamaa, Negar Naseh, Balsam Karam, Ida Börjel and Loretto Villalobos. In consultation with Gustafsson Fürst, Jonas Williamsson has designed the book in relation to the sculptures and the benches, where the book has been placed.

The contributing writers have departed from Gustafsson Fürst’s topics explored in Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue and interpreted it freely based on their own experiences and fields of interest. In “Dripsa Dickadejor”, Ida Börjel has brought together writers that she has “read and read” with ideas on how languages are used in various situations. Negar Naseh’s story “Vinden slår” (The Wind Beats) begins at a maternity ward and the naming of a newborn, while Lars Raatamaa’s “Fragmentvers” (Fragment verse) is, as the title indicates, a collection of fragments. “Stum” (Mute) is the title of Loretto Villalobo’s essay about having to leave one’s mother tongue as a child and end up, as an adult, between languages. The point of departure for Balsam Karam’s “Avståndsmätning” (Distance measuring) is the Turkish-Kurdish conflict and how language violence is committed. Sara Abdollahi writes in the introduction: “The collective work on Stridsskrift is part of a larger whole. Beyond a nationally closed linguistic non-community, and loosely joined, in conjunction with the artwork, it collectively upholds an integrity and a musicality in order to resist a given centre.”

Stridsskrift is available for order for 100 SEK including postage. Send your order to accelerator@su.se for information about payment and delivery options. The book is also available at the following retailers: Konst-ig, Aspudden’s book store, Hedengren’s book store, Söderbokhandeln, Rönnells antikvariat (Stockholm).

Researcher collaborations

In the process of producing the exhibition for Accelerator, Johanna Gustafsson Fürst met with language researchers at Stockholm University who generously shared their research. Stockholm University has long defended and upheld a strong position in foreign-language teaching, language didactics and linguistics. The research, and not least the researchers in language didactics and multilingualism who have been involved in the exhibition, agree that mother-tongue education promotes further language learning. In collaboration with researchers at the university, Accelerator will present a series of talks based on the exhibition’s central issues.

About Johanna Gustafsson Fürst

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst is born in 1973 and lives and works in Stockholm. She has an MFA from the Royal Institute of Fine Arts in Stockholm (2003). Fürst has been exhibited both in Sweden and internationally, and is represented by Belenius Gallery in Stockholm. In 2017, she received the Friends of Moderna Museets’s Sculpture Prize, followed by an extensive solo exhibition.

Credits

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst, Artist

Exhibition team Accelerator

Therese Kellner, Curator

Richard Julin, Artistic Director Accelerator

Tove Nilson, Communications Manager

Erik Wijkström, Exhibition Technician

Stridsskrift

Sara Abdollahi, Editor

Jonas Williamsson, Graphic designer

Authors: Ida Börjel, Balsam Karam, Negar Naseh, Lars Raattamaa and Loretto Villalobos

Collaborators to the artist

Eva Arnqvist, Artist

Gustaf Nordenskiöld, Artist

Lisa Torell, Artist

Malin Sternesjö, Artist

The artist wishes to thank:

Sara Abdollahi, Author

Axel Andersson, Author

Henrik Eriksson, Artist

Christina Fürst

Thomas Gustafsson

Hans Isaksson, Artist

Åsa Jungnelius, Artist

Jarmo Lainio, Professor of Finnish, Stockholm University

Inger Lindberg, Professor emerita, Department of Language Education, Stockholm University

Mona Mörtlund, Poet and language activist

Malin Nordström, Artist

Liv Strand, Artist

Erik Torvén, Architect

Jonas Williamsson, Graphic designer

Lena Ylipää, Artist

Karin Ylipää, Teacher

Gallery Niklas Belenius

Installation view from the first part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst’s exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst “VOX” (detail), 2020. Installation view from the the first part of the exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst “VOX” (detail), 2020. Installation view from the first part of the exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst “VOX” (detail), 2020. Installation view from the first part of the exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst “L/anguish–But if the Word Gags, Does Not Nourish, Bite it Off, 2019. Installation view from the first part of the exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Johanna Gustafsson Fürst “The Mothertongue”, 2019. Installation view from the the first part of the exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.

Installation view from the second part of Johanna Gustafsson Fürst’s exhibition “Graft the Words, Whip My Tongue” at Accelerator 2020. Photo: Christian Saltas.